Table of Contents

BasICColor desktop images and monitor test images v3.0 (6,5 MB). desktop images (Mac OSX and Windows). for Gamma 1.8, Gamma 2.2, LStar, sRGB. monitor test images (Mac OSX and Windows). homogeneity, gradation Files. BasICColor test images 2007 (8,6 MB). UniversalSmoothnessTest-en.tif. SRGB: NKsRGB.icm (Windows)/Nikon sRGB 4.0.0 (Mac OS) This RGB profile is used in the majority of Windows monitors. It closely resembles the RGB commonly used in color television, and is also used in the digital television broadcasting system that is on its way to becoming the industry standard in the United States of America.

- Basic Examples

- Conversion Errors

Quick Overview

This article provides details on how macOS color space conversion affects the values displayed in color meter utilities. Let's start by listing common mistakes made by developers:

A color can be identified by it's red, green, and blue values.

False. A color needs both coordinates and a color space (such as “my monitor's space” or “sRGB”) to be identified. While many web developers would say #ff0000 is red, it may be bright purple or green in a contrived space.

CSS colors correspond to my monitor's color space.

False. Per the CSS Color Module standard, colors are specified in the sRGB color space. Historically, however, browsers haven't color-corrected CSS colors. Safari 9 correctly treats CSS colors as sRGB and Chrome has an open issue to fix this.

Cocoa's “Device RGB color space” corresponds to my monitor's color space.

False. Starting in Mountain Lion 10.8,NSDeviceRGBColorSpace is treated as sRGB. See WWDC 2012 Session 523: “Best Practices for Color Management”.I can use a system-wide color meter to see an image file's RGB data.

False. You can use a color meter to approximate the file's original data, but there is no guarantee that one or more lossy color conversions haven't already occured. In order to see the file's original data, you need open the file in an image editor and use its built-in color meter or eyedropper tool. Note that even then, the data may not be accurate, as system image APIs may have performed a color conversion upon opening.Apple uses sRGB displays — hence, my display's native values are the same as sRGB.

False. While Apple displays in the 2012-2015 timeframe were close to sRGB, minor errors would still occur. In late 2015, Apple introduced iMacs using wider-gamut displays. Trying to use native values from these displays in an sRGB context will result in noticeably incorrect colors.Due to color conversion, a system-wide color meter is useless.

False. As long as a meter displays values in a standard color space (such as sRGB) and reports potential clipping issues, the meter should be accurate for most development purposes. The development environment must perform proper color management and use the same standard color space, however.My recommendation is to always keep color meters and development tools in sRGB.

If you are using a near-sRGB display, you can set its profile to be sRGB. This results in a slight loss of color accuracy in exchange for less clipping errors.

If you are on a wide-gamut display, you should instead use the native color profile and live with sRGB→Native rounding errors. If you are a web developer on a wide-gamut display, use Safari for development rather than Chrome (until it treats CSS colors as sRGB).

Article Assumptions

A basic understanding of digital images and color management is assumed:

- An image comprises pixels arranged in a two dimensional grid. Each pixelcomprises one or many channels.The channels used in most color images are “red”, “green”, and “blue”.

- Each channel of each pixel has a numeric value. Full intensity is commonly representedas 1.0, 100%, 255, or #ff (hexadecimal). Zero intensity is commonly represented as0.0, 0%, 0, or #00.

- These intensity values are relative. For example, “100% red” in one imagemay be a different color than “100% red” in another image, which is differentthan “The most saturated red that an average human eye can detect”.

- A “color profile” contains measurements which can convert relativeintensity values to an absolute, measurable real-life color. If both arecording device (camera, scanner) and a reproduction device (monitor, printer)have accurate color profiles, and color profile information wasn't discarded during editing;the reproduced color should be an accurate representation of the original color.

- Each image may contain (“embed”) a color profile. If an image lacks a color profile,it will be displayed differently among devices and programs.

- It is very common for images to not contain color profiles.

If needed, please consult these excellent resources on colormanagement.

macOS Color Management

Each graphics buffer (bytes filled with image data) in macOS has an associatedcolor profile attached to it. If two buffers have different profiles, and the contents of one is drawn into the other;the system performs color conversion.

Consider a simple application which loads an image from disk and draws it into a window. A minimum of three buffers willbe used:

- The buffer corresponding to the loaded image file.

- The buffer corresponding to the application's window

- The buffer assigned to the system's monitor

All system-wide color utilities (including the default Digital Color Meter, my Classic Color Meter, and the system's Color Picker) access the contents of the last buffer (the one associated with a monitor). Any buffer prior to the last is ownedby the window's application and not accessible using macOS's public function calls.

As long as each buffer uses the same color profile, no color conversion occurs. This means that the value seen in a color meterutility is the same as the original value in the image file. However, when different profiles are involved, the value shown bya color meters will not be the same as the original value in the file.

In Snow Leopard 10.6 and prior, it was common for the profiles of all buffers to match,even when using multiple monitors. Thus, color meters commonly reflected the original imagefile's values.

In Lion 10.7, users with multiple monitors noticed that color meters “did notshow the correct value” when sampling off of the secondary display. This was due toa buffer being assigned the main display's color profile, and then being drawn into thesecondary display's buffer (thus resulting in a conversion).

In Mountain Lion 10.8, color management changed again. When an image lacks its own profile,the system now defaults to sRGB rather than themain display's color profile. This results in more frequent color conversions (and thus color metermismatches). Mountain Lion also changed the behavior of many color-related APIs. Calls such as NSColor's +colorWithDeviceRed:green:blue:alpha:were changed to return a color in the sRGB color space rather than the monitor's color space. (Specifically, NSDeviceRGBColorSpace is now treated equal to the sRGB space.)This is covered in WWDC 2012 Session 523: “Best Practices for Color Management”.

The behaviors mentioned above are guidelines — individual applications may use additional buffers and/orexplicitly assign color profiles. A test image is provided at the end of this articlewhich can be loaded in an application and then sampled using a color meter.

Basic Examples

Let's walk through a few basic examples. In all of these, an image without a color profile isdrawn directly to the screen and then sampled with a color meter utility. These examples do notshow the window's buffer, as it will have the same color profile as the display on which it islocated.

Example 1 - Lion 10.7: Image without profile, main display

1A — On Disk R 255 B 0 | Main Display profile R 255 B 0 | Main Display profile R 255 B 0 | “native values” R 255 B 0 |

Suppose that we have an image of a yellow box. The raw bytes of the file consist of a repeated pattern of the bytes [255, 255, 0] (pure yellow, or #ffff00). There is no color profile embedded in the image (Figure 1A).

When macOS loads our image into memory, no color space conversion is applied to the repeating pattern of [255, 255, 0]. However, the system needs to assign a color profile at this time. In versions of macOS prior to 10.8, when an image lacks an embedded profile, the main display's profile is assigned. Thus, in memory, our image is still [255, 255, 0], but now is in the main display's color space (Figure 1B).

When the image is drawn, macOS performs a color space conversion if the image's profile doesn't match the destination profile. In this example, we are viewing the image on the main display; thus, no conversion occurs (Figure 1C).

We now sample the color in our meter, with “native values” selected. Since no color space conversion occured, we see the original [255, 255, 0] values of the file (Figure 1D).

Example 2 - Lion 10.7: Image without color profile, second display

no color profile R 255 B 0 | Main Display profile R 255 B 0 | 2nd Display profile R 248 B 45 | “native values” R 252 B 45 | “Convert to main display” R 254 B 1 |

Let's take our yellow box image and move it to the second display. As in Example 1, the image contains a repeating pattern of [255, 255, 0] and has no embedded color profile (Figure 2A).

Again, when macOS initially loads our image into memory, no color space conversion is applied to the repeating pattern of [255, 255, 0]. However, it still needs to assign a color profile at this time. The operating system isn't psychic (yet), so it doesn't know that it will be rendering the image on the second display. Hence, the main display's profile is once again assigned (Figure 2B).

Now, when the image is drawn, a color space conversion to the second display's profile occurs. Due to the conversion, the RGB values no longer match the file (Figure 2C). When viewed in our color meter with “native values” selected, these screen values are used (Figure 2D).

By selecting “Convert to main display” in our color meter, we can apply another color space conversion back to the main display. Due to conversion errors, this value isn't the exact same as the original, but it's close.

Example 3 - Modern macOS: Image without profile

no color profile R 255 B 0 | sRGB profile R 255 B 0 | Main Display profile R 254 B 56 | “native values” R 254 B 56 | “Display in sRGB” R 255 B -2 |

Let's take our yellow box image and load it onto a modern (10.8+) version of macOS . As in the first two examples,the image on disk is a repeating pattern of [255, 255, 0]; and has no embedded color profile (Figure 3A).

In Mountain Lion, when an image lacks an embedded profile, the sRGB color space is assigned. Thus, in memory, our image is still [255, 255, 0], but now is in sRGB. (Figure 3B).

When the image is drawn to either display, macOS will perform a color space conversion (Figure 3C). These converted values will also appear in our meter (Figure 3D).

By selecting “Display in sRGB” in our meter, we can convert back to the original values in the file. Again, due to the conversion errors, it's not the same as the original, but close (Figure 3E).

Conversion Errors

Unfortuately, when colors are stored as bytes ranging from 0-255, each color conversion can lose information. This results in two types of errors: rounding and clipping.

Example 4 - Rounding Errors

R 255 B 0 | (raw) R 248.49 B 44.55 | (rounded) R 248 B 45 | (raw) R 254.49 B 0.53 | (rounded) R 254 B 1 |

Rounding errors occur due to the color conversion rounding a raw floating-point value back into a 0-255 integer value.

Let's take a closer look at the color conversion from Example 2. When we applied the Main Display → 2nd Display color conversion, [255, 255, 0] seemingly transformed into [248, 255, 45]. However, behind the scenes, it actually transformed into [248.49, 255.06, 44.55], which was then rounded.

This is fine, as [248, 255, 45] is the closest color on the 2nd Display. However, our reverse 2nd Display → Main Display conversion has no way of using the non-rounded values. The final result is close to the original value, but not exact.

Example 5 - Clipping Errors

Clipping errors can be more severe. They occur when a color conversion takes a value above 255 or below 0. To demonstrate an extreme case, we will use the following color profiles, which use noticeably different positions for the green point.

Let's convert [0, 255, 0] (pure green, or #00ff00) in sRGB to the Main Display's profile.

R 0 B 0 | (raw) R -90.09 B 83.41 | (rounded & clipped) R 0 B 83 | (raw) R 86.37 B -4.90 | (rounded & clipped) R 86 B 0 |

Due to the different green points, each conversion will alter the red and blue values significantly. In Figure 5B, red is taken to -90.09. Since we are storing these values in bytes ranging from 0-255, red is cropped to 0 (Figure 5C).

While this is the closet color representation on the Main Display, the dramatic information loss causes issues if we want to convert back to sRGB. In Figure 4D, the reverse conversion bumps red to 86.37 and drops blue to -4.90. Once clipped, this results in a more yellowish-green color than we originally had.

Color Faker (Do Not Use)

When Mountain Lion 10.8 introduced the new assume-no-profile-is-sRGB behavior, I wrote a utilitycalled ColorFaker which attempted to restore theLion 10.7 behavior. It was a hack, but worked as a stopgap during 10.8 and 10.9.

In Yosemite 10.10, ColorFaker causes crashes. In El Capitan 10.11, System Integrity Protection renders it completely useless.

I have since discontinued development and strongly recommend against using ColorFaker.

Test Image & HTML Table

When in doubt, sample the color management behavior of an application yourself. Drag the following test image to your desktop,then open it in a target application. Set your color meter to “Use native values” and move the mouse cursorover each color swatch. If the values reported by the meter align with the text printed in the file, no color conversion isbeing applied.

Also provided is an HTML table stylized with CSS background colors. This can be used in combination with a color meter to determine how browsers handle CSS colors:| FF,00,00 | 00,FF,00 | 00,00,FF | FF,FF,FF |

| AA,00,00 | 00,AA,00 | 00,00,AA | AA,AA,AA |

| FF,00,FF | FF,FF,00 | 00,FF,FF | 00,00,00 |

| 55,00,55 | 55,55,00 | 00,55,55 | 55,55,55 |

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is Apple doing this?

I have no knowledge of Apple's goals, but I suspect they desire to offer wider-gamut displays to consumers (with the late 2015 Retina iMac as the first example). If you could install Snow Leopard 10.6 on one of these machines, the old “use the display profile for untagged colors” behavior would result in oversaturation due to the wider DCI-P3 color space.

In addition, these changes align macOS with other operating systems and web standards. For example, the CSS Color Module specification has always stated that colors are in sRGB.

What could Apple do better?

There are different approaches that Apple could take, but they all involve trade-offs.

At the time of this writing (10.11), most buffers use a bit depth of 8 bits per channel, with a value range of 0 for pure black to 255 for pure white. If the bit depth were increased to 10 or 12 bits per channel, rounding errors could be less severe. If the value range were altered to allow sub-black and super-white values, clipping errors would be reduced (although there should be no clipping when going from sRGB to DCI-P3). However, these changes would also increase memory footprint and decrease graphics performance.

Alternatively, the system could use sRGB for all buffers. This would eliminate many conversion errors, but would prevent deep-color images from displaying as-intended on wider-gamut devices. There could also be double conversions (once to sRGB, once to the display's space), which would decrease performance. This isn't a good solution for consumers, as it effectively turns the DCI-P3 display into an sRGB one; however, it would be great for developers/designers that need to work in sRGB.

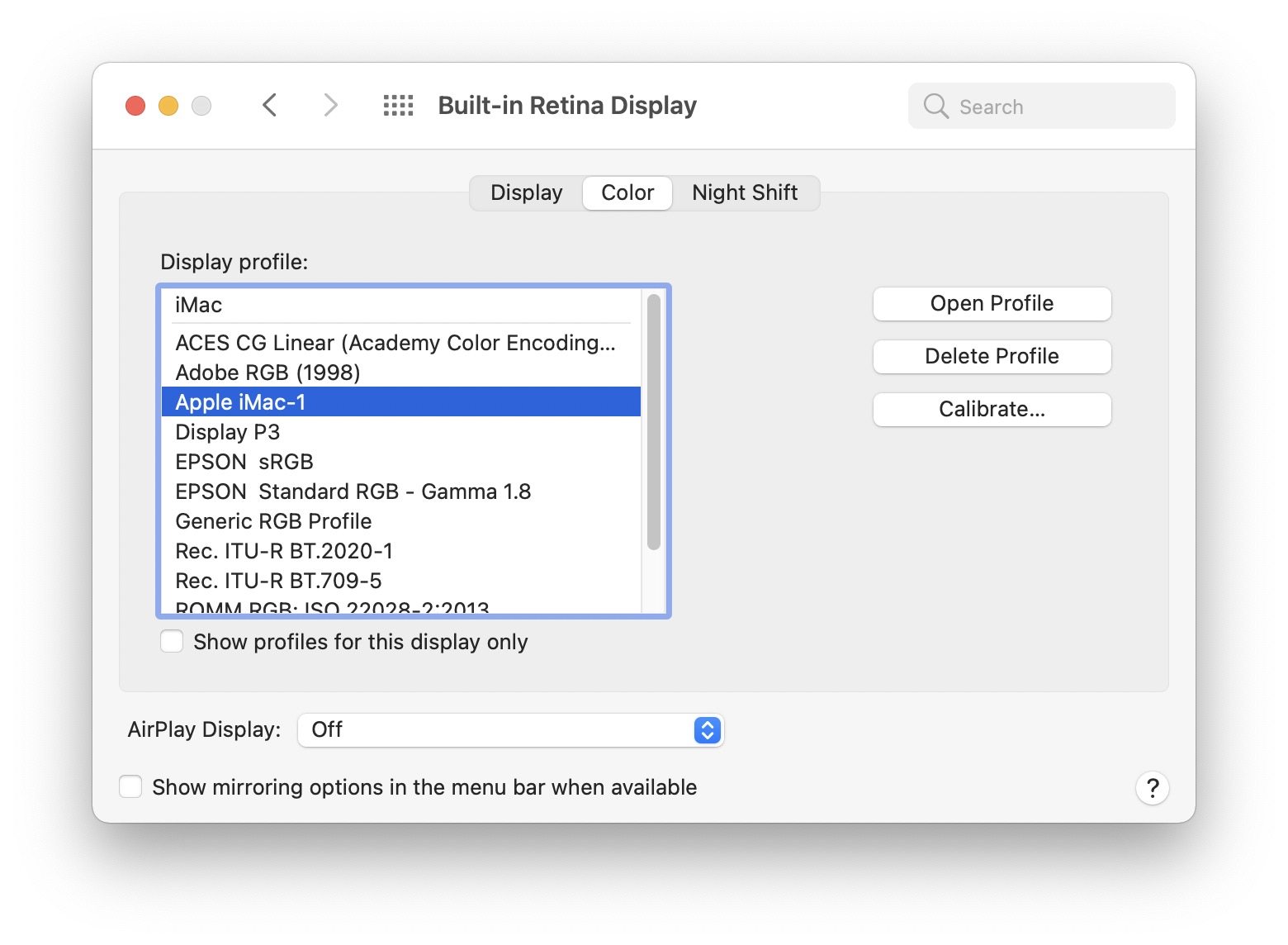

Can I select sRGB as my monitor's profile to prevent conversions?

Yes, if you specify sRGB as your monitors display profile, several color conversions will be eliminated. However, the actual color accuracy of your display will be compromised.

If you are on a near-sRGB display, such as the Late 2014 Retina iMac or Late 2013 Retina MacBook Pro, the accuracy loss is small and likely acceptable. If you are on a wide-gamut display, such as the P3 display in the Late 2015 Retina iMac, this technique will result in oversaturated colors.

Additional Reading

- Cambridge in Colour articles

- Wikipedia Articles

- Other Links

Mac Srgb Color Profile

THE COLOR THEORY AT WORK HERE

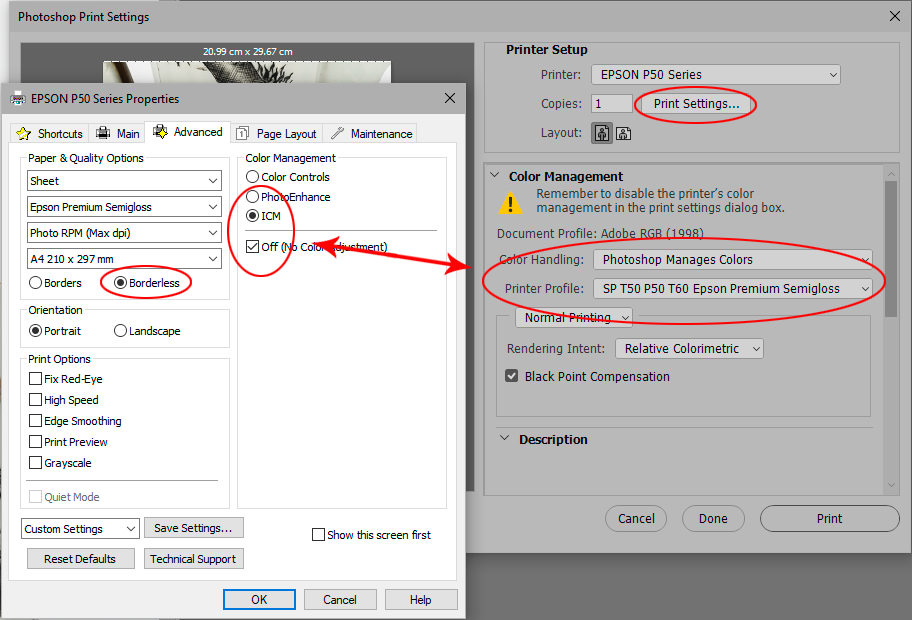

A color-managed Web browser or color-managed application like Safari, iPhoto, Preview.app, Photoshop, Aperture, Lightroom HONORS (or reads) the embedded ICC profile and CONVERTS (corrects) the source color to the monitor profile for a theoretical display of 'true color' — all three above tagged files will match in color-managed web browsers.

Download Srgb Color Profile Macbook

WINDOWS 'HALF' COLOR MANAGEMENT DISCLAIMER (Source> sRGB): Take notice some Windows color-managed Web browsers only Convert tagged elements to sRGB (not the monitor profile). My tests (late 2012) included so-called 'color-managed' Windows versions of Chrome, Safari, Internet Explorer IE, which all all displayed the PDI tagged reference images with oversaturated reds on a wide gamut monitor. Firefox with its Value1 enabled was the only Windows browser that displayed with 'Full Color Management' (Source> Monitor).

Software updates and user settings may change how my reference images display so be sure to perform your own tests to prove or disprove my theories on your devices.

Download Srgb Color Profile Macbook Pro

Non-color-managed browsers are simply applying (for all practical purposes) the same DEFAULT PROFILE to all three pairs of of images — so both boxes will display exactly the same (with the same noticeable changes between each rollover).